February 2026

On 28 August 1975, fifteen days before the 23rd San Sebastian Festival’s inauguration, the first in a series of summary courts-martial began in Burgos, which would end with 11 ETA and FRAP militants being sentenced to death. In Burgos, a military court would convict Jose Antonio Garmendia Artola and Ángel Otaegui, and the news would spread like wildfire, even internationally, where coexistence with a fascist state – the last dictatorship in Europe’s – was becoming increasingly unsustainable.

Besides a register of popular protests in almost all major cities and capitals, Mexican President Luis Echeverría Álvarez demanded that Spain be expelled from the UN, cancelled flights between Madrid and Mexico City, and closed Spain’s trade office in the country and the EFE news agency’s office. The governments of Norway, United Kingdom and the Netherlands recalled their ambassadors in Madrid for consultations. In Copenhagen, the Atlantic Alliance approved a motion of protest and urged member countries not to do anything that could favour Spain’s entry into that organization. Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palmer took the streets of Stockholm with a collection box to protest the sentences and to ask for funds to promote the democratization of Spain.

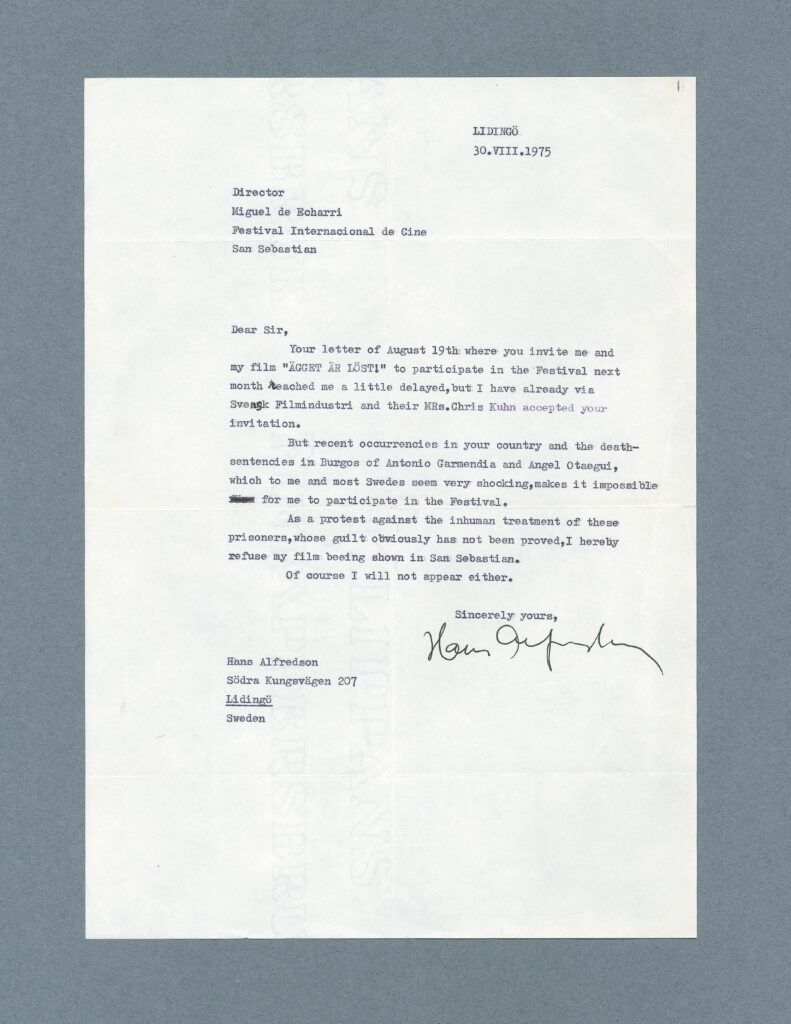

In that turbulent climate, filmmakers, actors and guests saw how the San Sebastian Festival, the most important diplomatic and cultural body of the State, was finalizing the details of its opening ceremony completely oblivious to the protests and social demands. It was precisely from the Swedish island of Lidingö that the first letter of rejection of the event from a filmmaker arrived on August 30, just two days after the Burgos Council. In his letter, Hans Alfredson detailed how the recent events in Spain and the death sentenced of Garmendia and Otaegui had shocked both him and the Swedish people, and how the situation prevented him from participating in the Festival, which had invited him with his first film Ägget är löst! (The Softening of the Egg), a film about the dynamic work of factory, starring Max von Sydow. Alfredson withdrew his film from competition in ‘protest against the inhumane treatment of these prisoners, whose guilt obviously has not been proven. Of course, I will not appear either’. The film was released commercially, ruling out a festival premiere.

Alfredson’s letter was followed by dozens of letters and telegrams from various personalities, film institutes and film crews, adding to the refusal to attend San Sebastián. On 27 September 1975, the regime carried out the executions by firing squad of Ángel Otaegui, Juan Paredes Manot ‘Txiki’, José Luis Sánchez Bravo, Ramón García Sanz and José Humberto Baena Alonso, whose death sentences had not been commuted.

Full description sheet

Document

Letter of refusal from director and actor Hans Alfredson to participate in the Festival following the death sentences of Antonio Garmendia and Angel Otaegui

Identity statement area

ID: 47553

Catalogue number: AO1975-1976.0145

Location: M02.B01.C01

Classification scheme: 4.1.4. International directors

Title: Letter of refusal from director and actor Hans Alfredson to participate in the Festival following the death sentences of Antonio Garmendia and Angel Otaegui

Date of creation: 1975-08-30

Level of description: Simple documentary unit

Extent and medium of the unit of description: 1 document

Context area

Producer: Hans Alfredson

Conditions of access and use area

Conditions governing access: Conditions governing access

Conditions governing reproduction: Conditions governing reproduction

Control area

Preservation: Anna Ferrer, Andrea Sánchez

Cataloguing: Edurne Arocena (Ereiten)

Other documents of the month

[+]

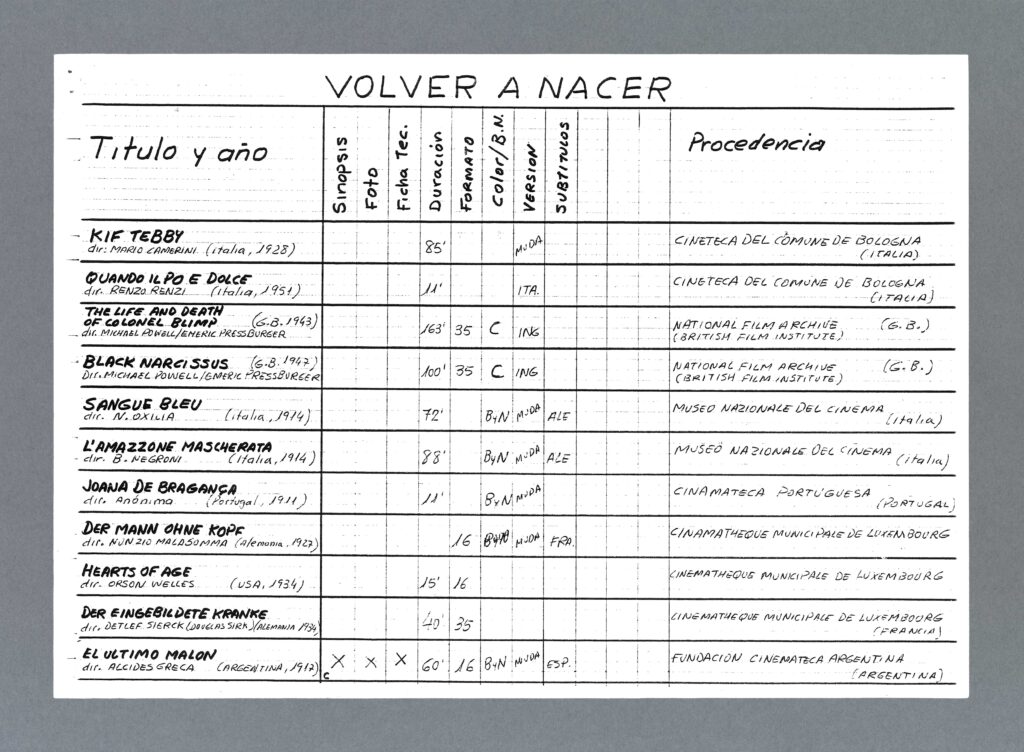

Internal programming document relating to the retrospectives “Volver a nacer” and “Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast” (1990) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

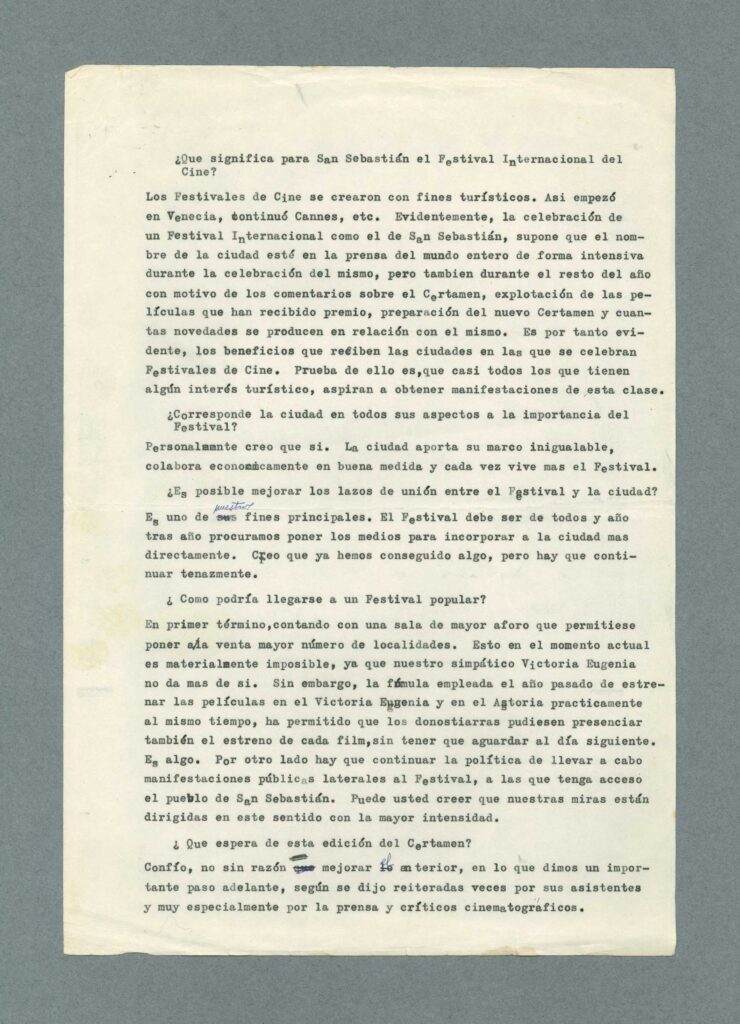

Interview with the competition organisers prior to the 16th edition in 1968 (1968) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

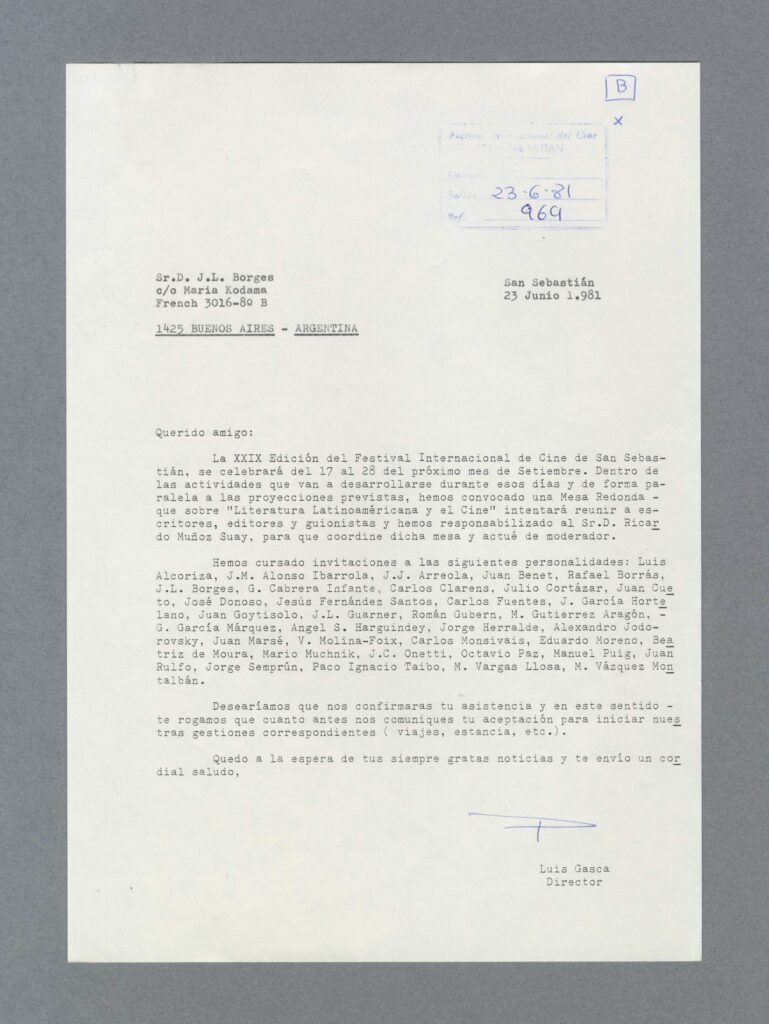

Letter from Luis Gasca to Jorge Luis Borges on the occasion of his participation in the round table discussion ‘Latin American Literature and Cinema’ (1981) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

Actress Gina Lollobrigida presenting the San Sebastian Award for Best Female Performance to the distributor Procinor for “A Woman Under the Influence” (1975) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

The actress Josefa Flores González, better known as Marisol or Pepa Flores, at the Hotel María Cristina (1960) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

Anne Bancroft at the Victoria Eugenia Theatre’s boxes entrance during the presentation of the film “The Miracle Worker” (Arthur Penn) (1962) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

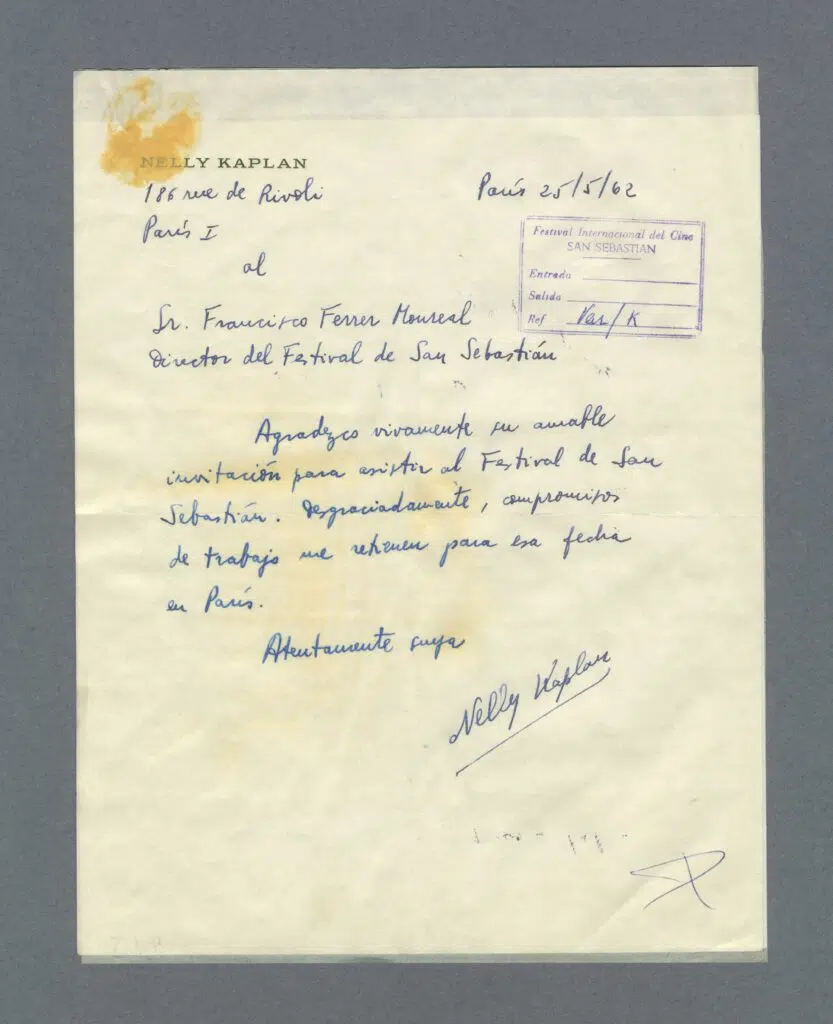

Letter from Nelly Kaplan to Francisco Ferrer on the invitation to the festival (1962) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

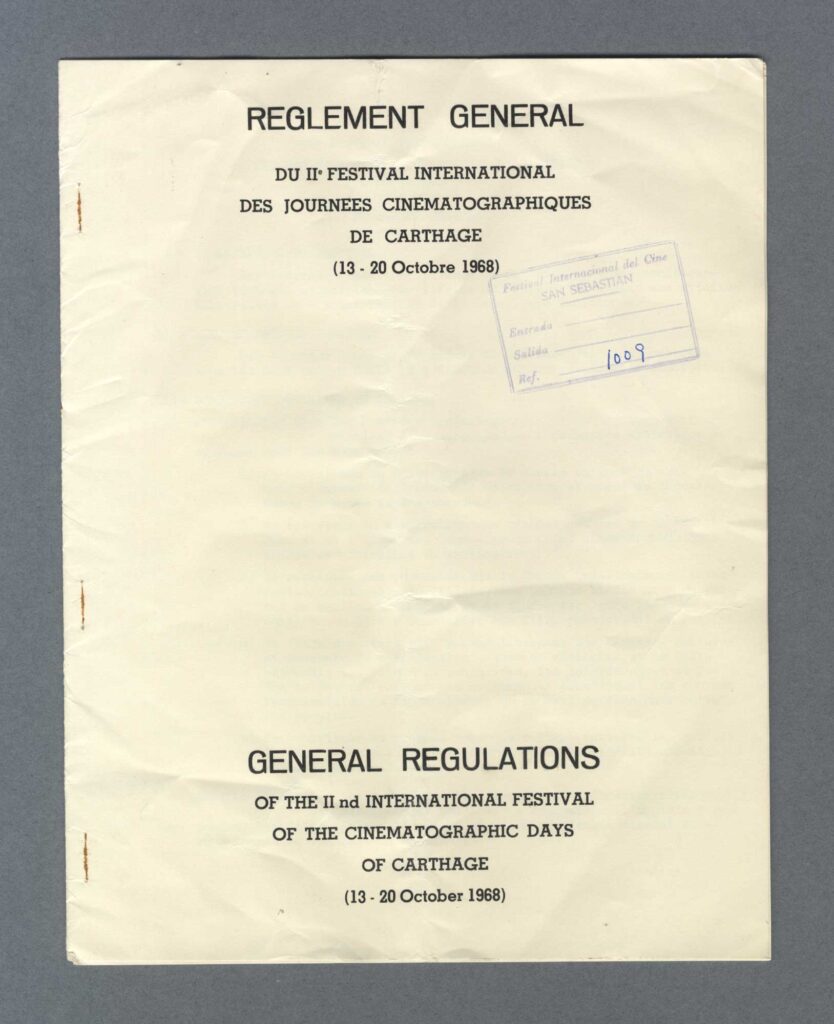

Regulations of the II Cartago International Film Festival (1968) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

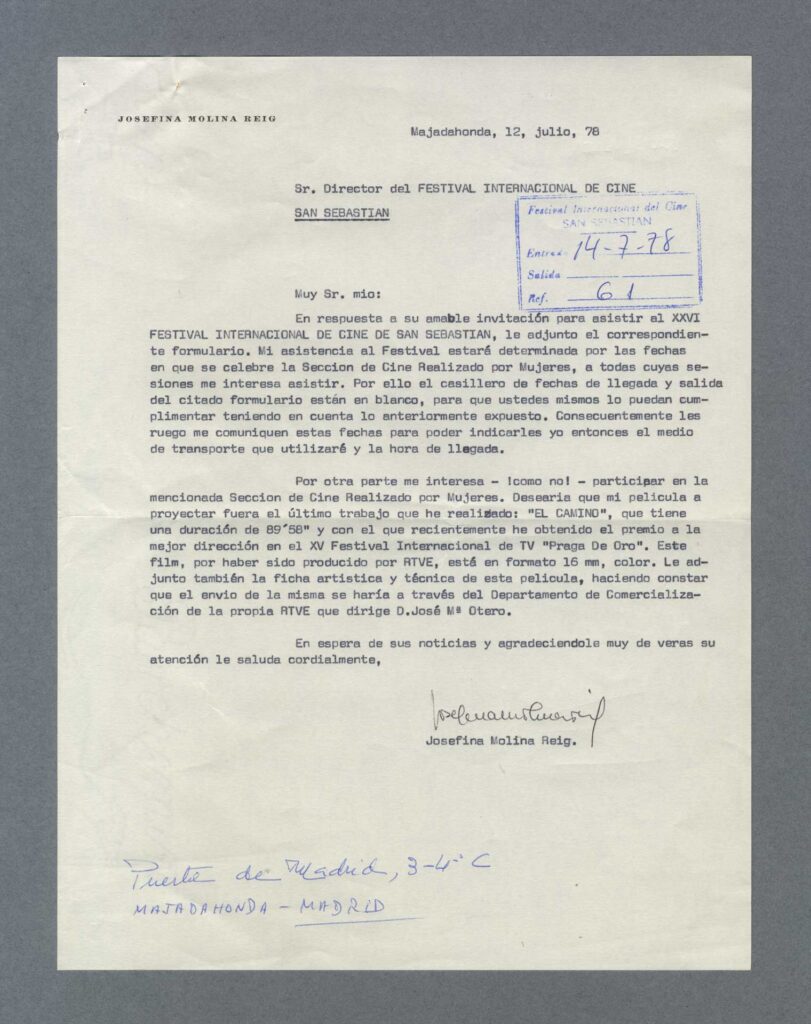

Letter from Josefina Molina to the Festival organisers (1978) San Sebastian Festival Archive [+]

[+]

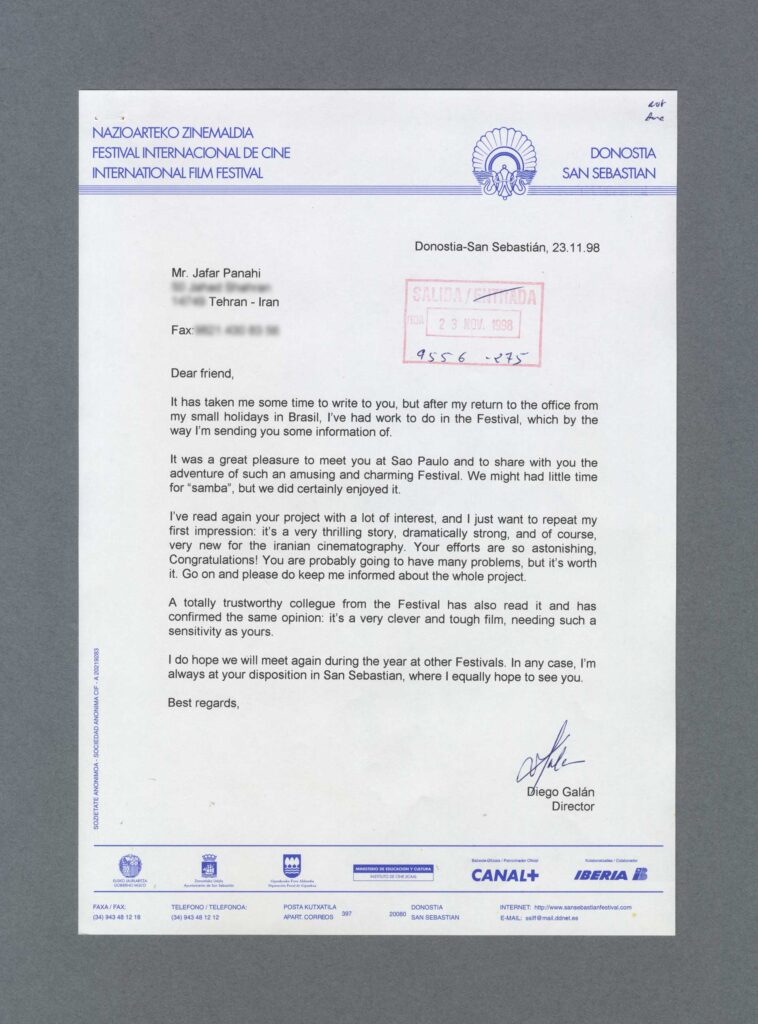

Letter from Diego Galán to film director Jafar Panahi (1998) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

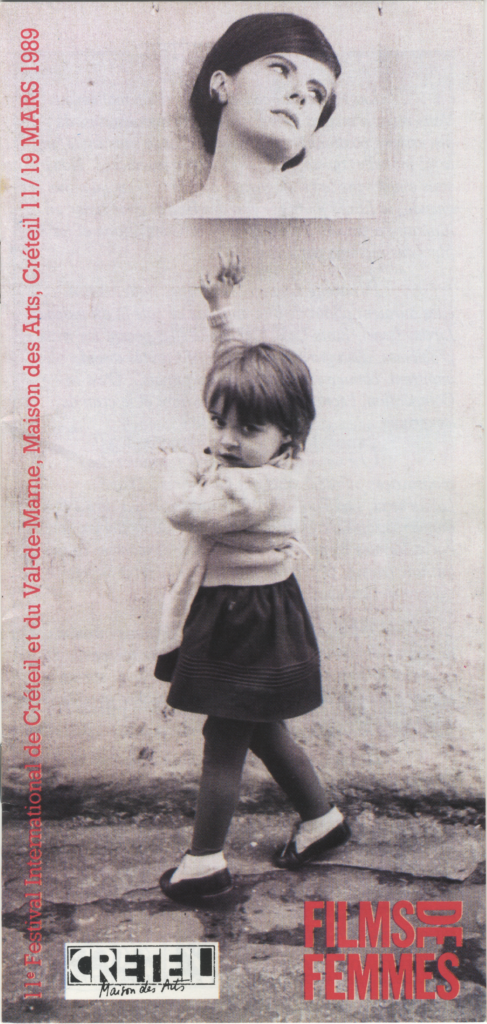

Program for the 11th edition of the Festival International de Films de Femmes de Créteil et du Val de Marne (1989) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

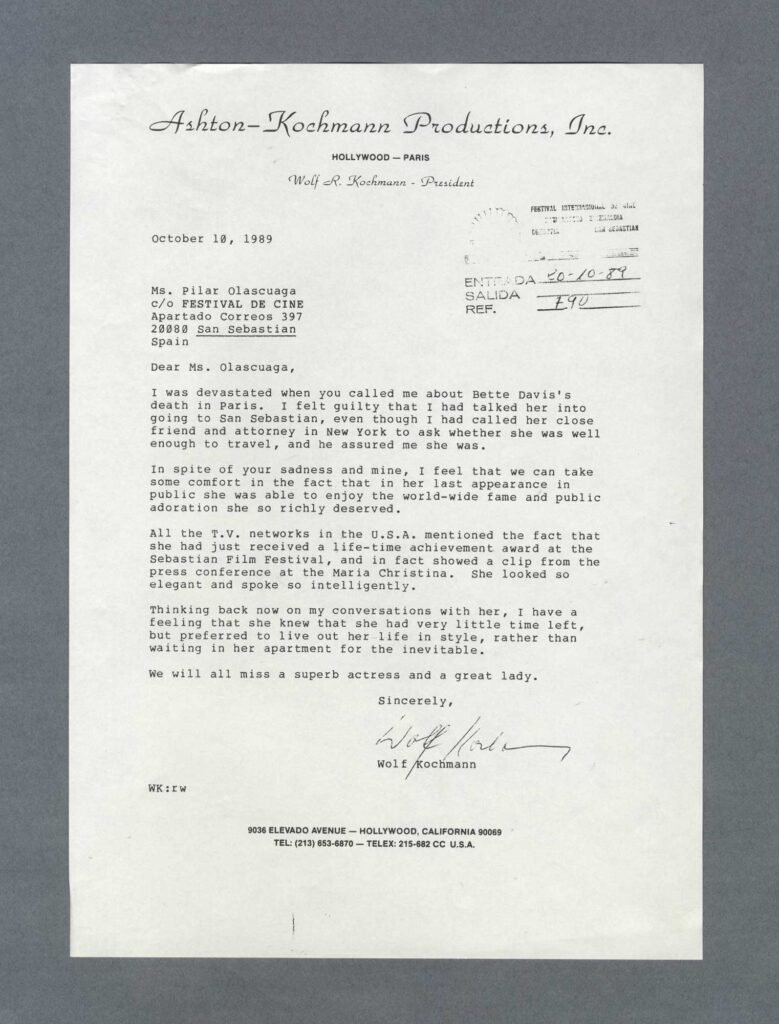

Letter from Wolf Kochmann to Pilar Olascoaga on the death of Bette Davis (1989) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

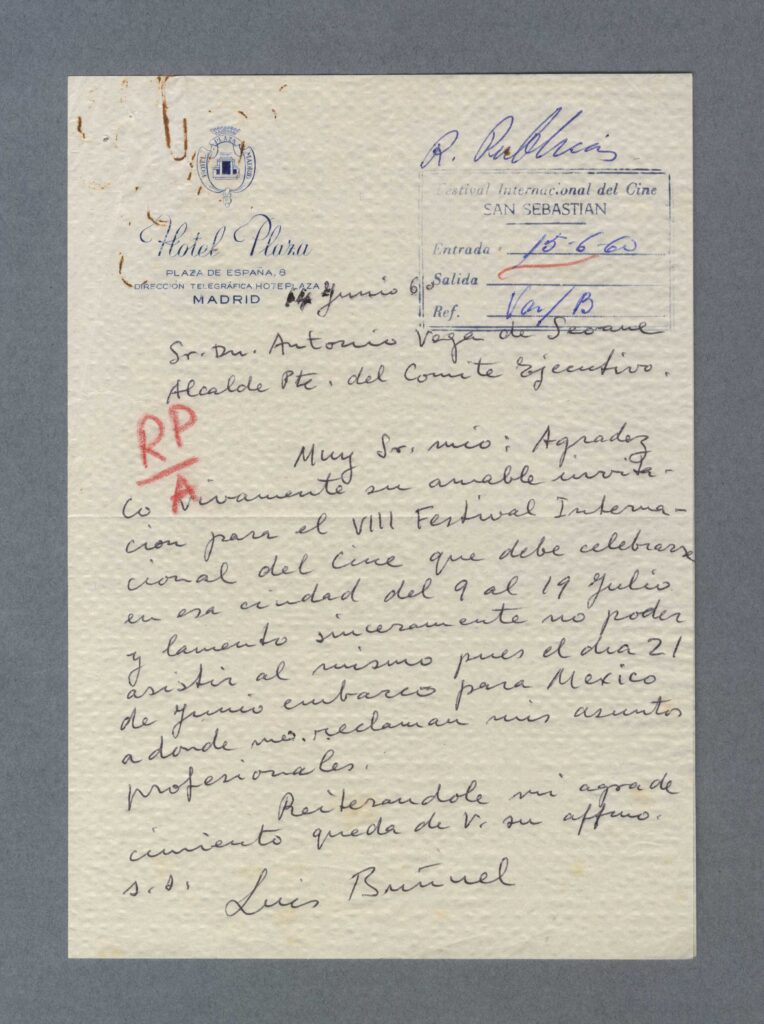

Letter from Luis Buñuel to the Mayor of San Sebastián Antonio Vega de Seoane (1960) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

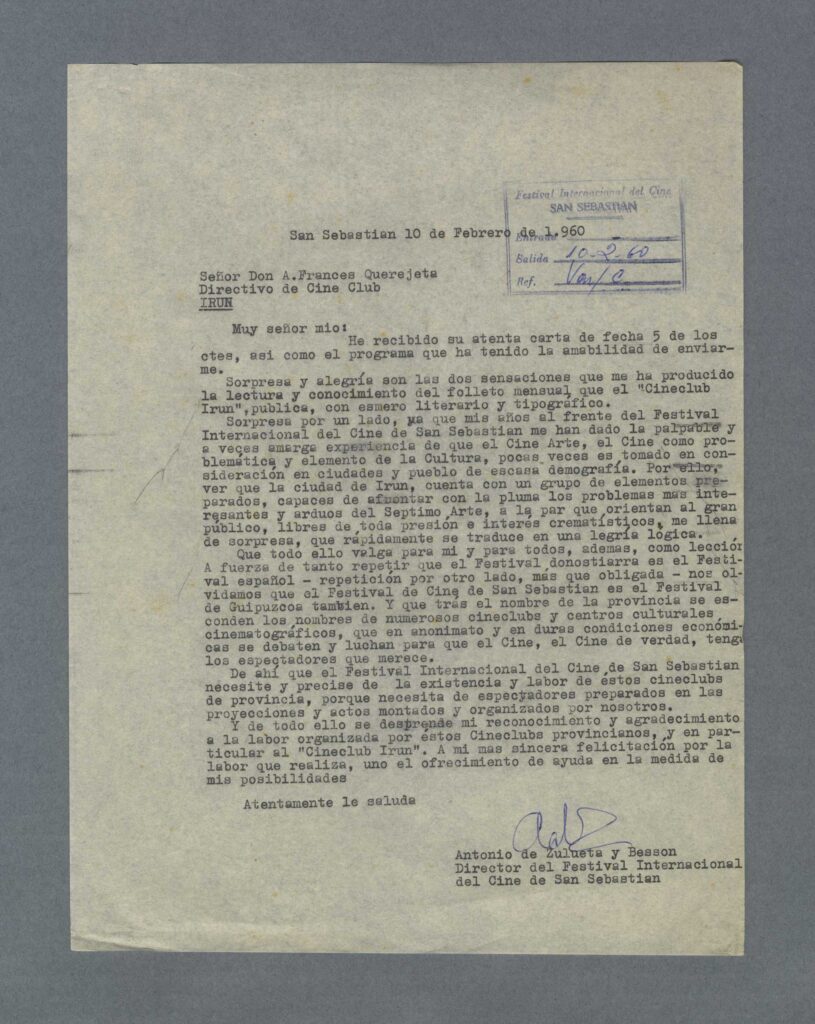

Letter sent by Antonio de Zulueta y Besson to the Cineclub Irún accepting to collaborate with them (1960) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

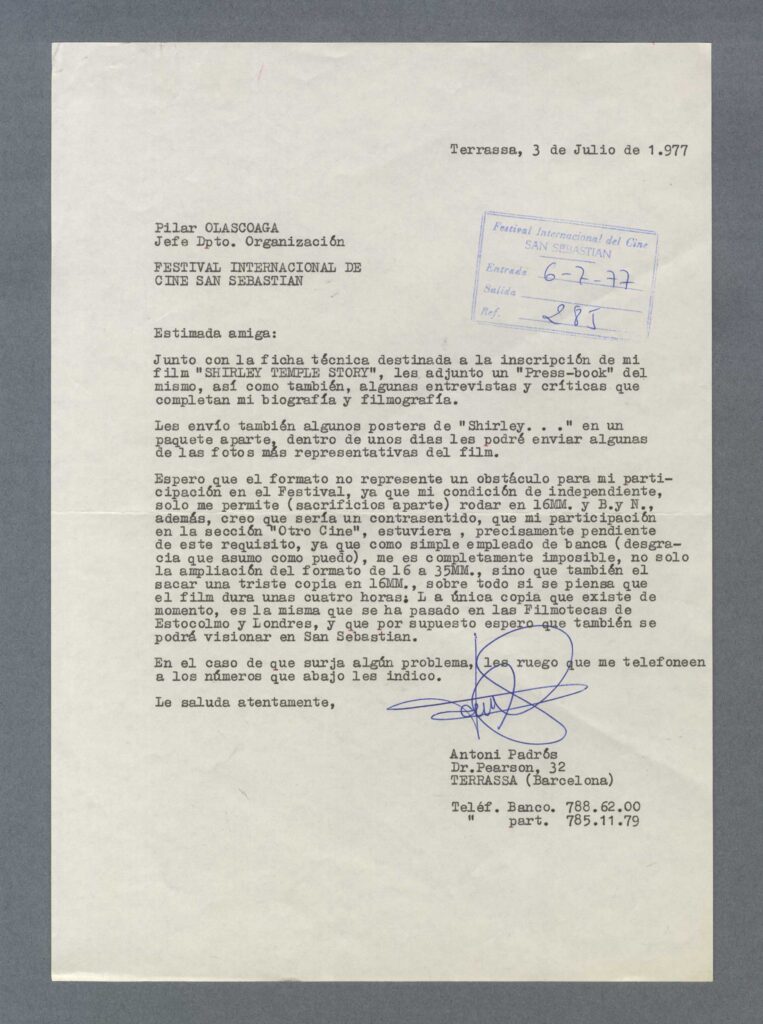

Letter from underground filmmaker Antoni Padrós to Pilar Olascoaga (1977) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]