Digital collections

Digital collections

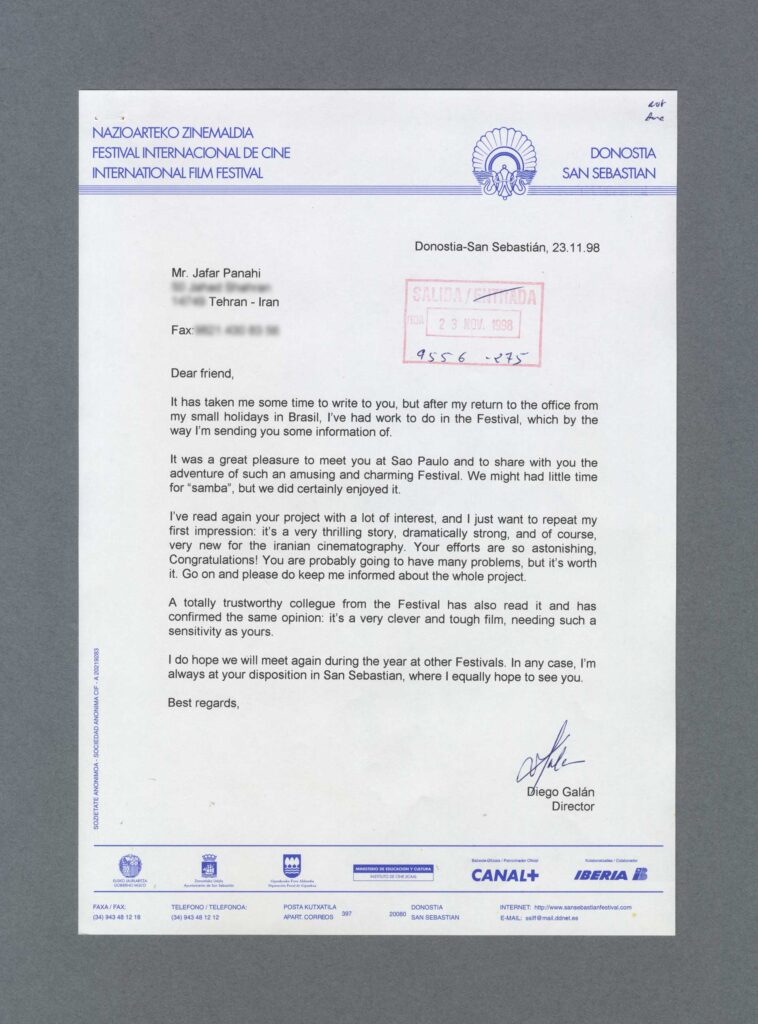

Letter from Diego Galán to film director Jafar Panahi

May 2024

In November 1998, by then in his second period as director of the San Sebastian Festival, Diego Galán sent a fax to the Iranian moviemaker Jafar Panahi. While the tone of the communication, sent to a Teheran address, reveals personal relationship between the director and the moviemaker, it also hints at the political climate and cultural persecution in that Asian country at the doors of the new millennium.

As we can see from the correspondence, Galán and Panahi had previously met one another at the 22nd edition of the São Paulo International Film Festival (founded at the height of the military dictatorship), where the former was a member of the jury and the latter was presenting his second feature The Mirror (Ayné, 1997), winner of the Golden Leopard at the Locarno Festival.

It was there that Galán would hear first hand about the projects that the Iranian moviemaker was trying to get off the ground. On his return to San Sebastián, Galán joined a “trusted colleague at the festival” to read a project delivered to him by the moviemaker in Brazil, impressing upon him that “despite the fact that it would probably have problems, it was worthwhile”, referring to potential clashes with the censorship apparatus of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The film, premiered with the title of The Circle (Dayereh, 2000), would become one of Jafar Panahi’s most award-winning and acclaimed projects, carrying off the Venice Festival’s highest accolade and closing the circle in San Sebastian when he came here to collect the award given by the international critics for best film of the year.

Over the years, Panahi has continued his struggle against the Iranian regime, using the cinema as a political tool. A statement openly declaring his support of the Green Wave movement, launched in 2009 as a form of opposition to the presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, was followed by his arrest. Two years later, the Tehran Court of Appeal confirmed his sentence, which included the prohibition of making films, traveling outside the country or talking to the press for a period of 20 years.

Until his release on bail in 2023, Panahi had made eight underground projects. His model of production – limited to the strictest confinement – has irremediably prompted the forms of his cinema to mutate in all possible directions, acting as a mirror between his political and cinematic militancy.

Full description sheet

Document

Communication with film director Jafar Panahi

Identity statement area

ID: 27210

Catalogue number: AO1998.0275

Location: M09.B05.C03

Classification scheme: 4.1.4. International directors

Title: Letter from Diego Galán to film director Jafar Panahi

Date of creation: 1998-11-23

Level of description: Simple documentary unit

Extent and medium of the unit of description: 1 document

Context area

Producer: Diego Galán

Content and structure area

Places: Donostia-San Sebastián, Teherán

Conditions of access and use area

Conditions governing access: Conditions governing access

Conditions governing reproduction: Conditions governing reproduction

Control area

Preservation: Anna Ferrer, Andrea Sánchez

Cataloguing: Edurne Arocena (Ereiten)

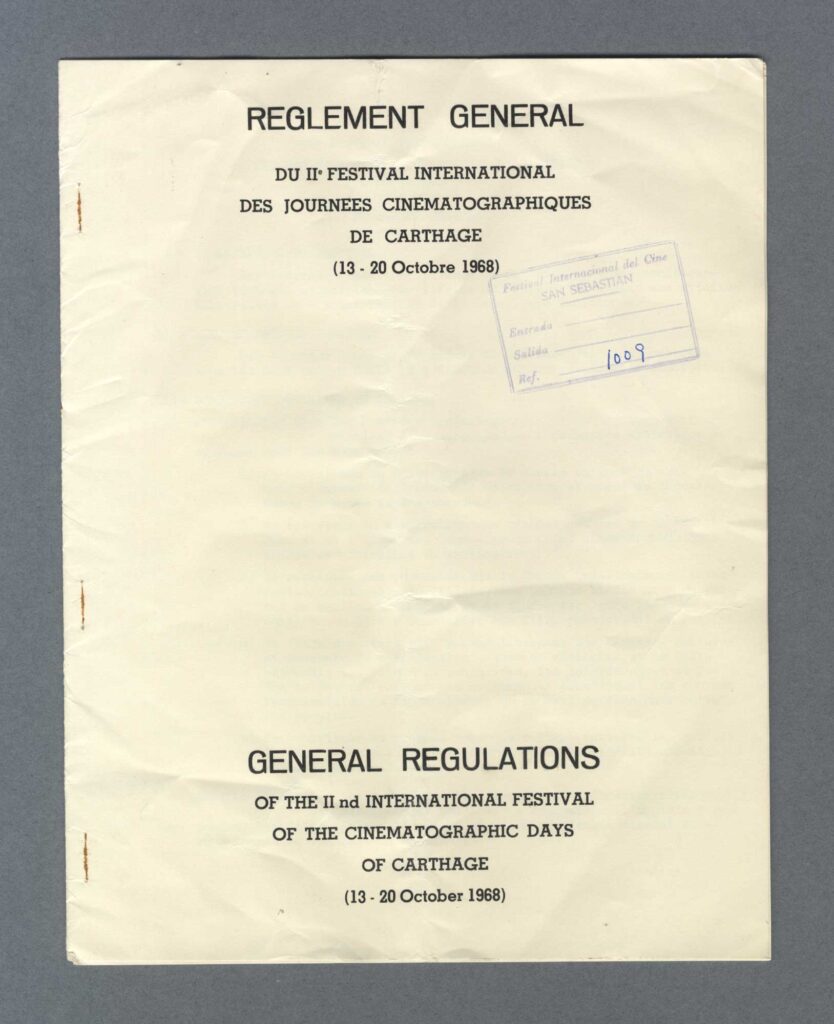

Other documents of the month

[+]

Anne Bancroft at the Victoria Eugenia Theatre’s boxes entrance during the presentation of the film “The Miracle Worker” (Arthur Penn) (1962) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

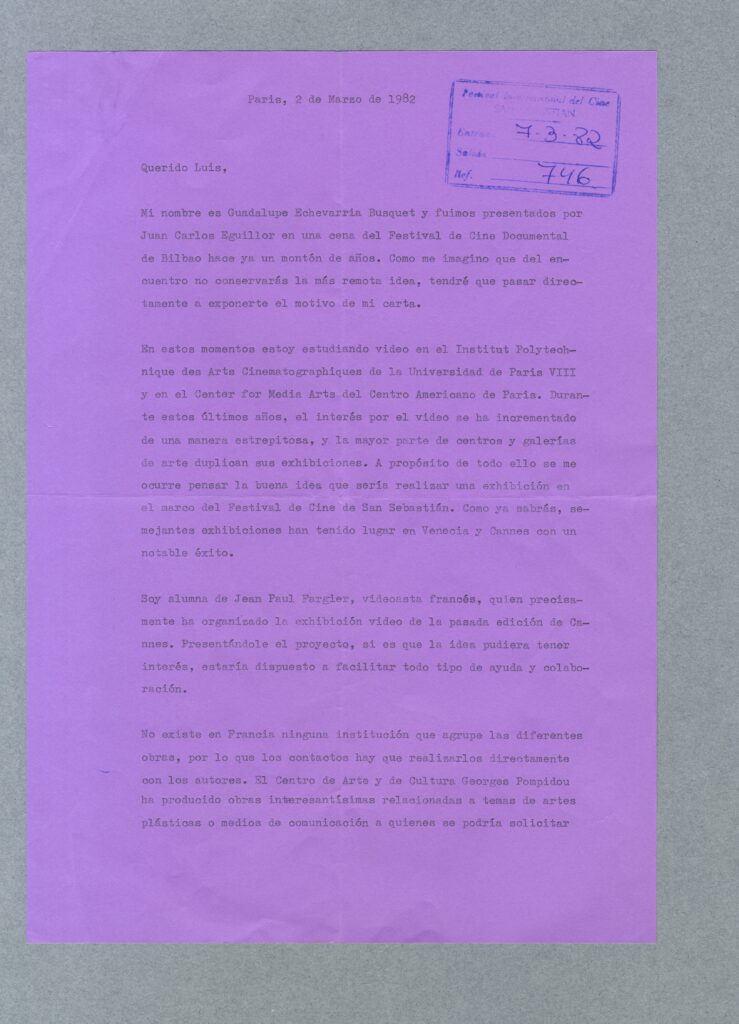

Letter from Nelly Kaplan to Francisco Ferrer on the invitation to the festival (1962) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

Regulations of the II Cartago International Film Festival (1968) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

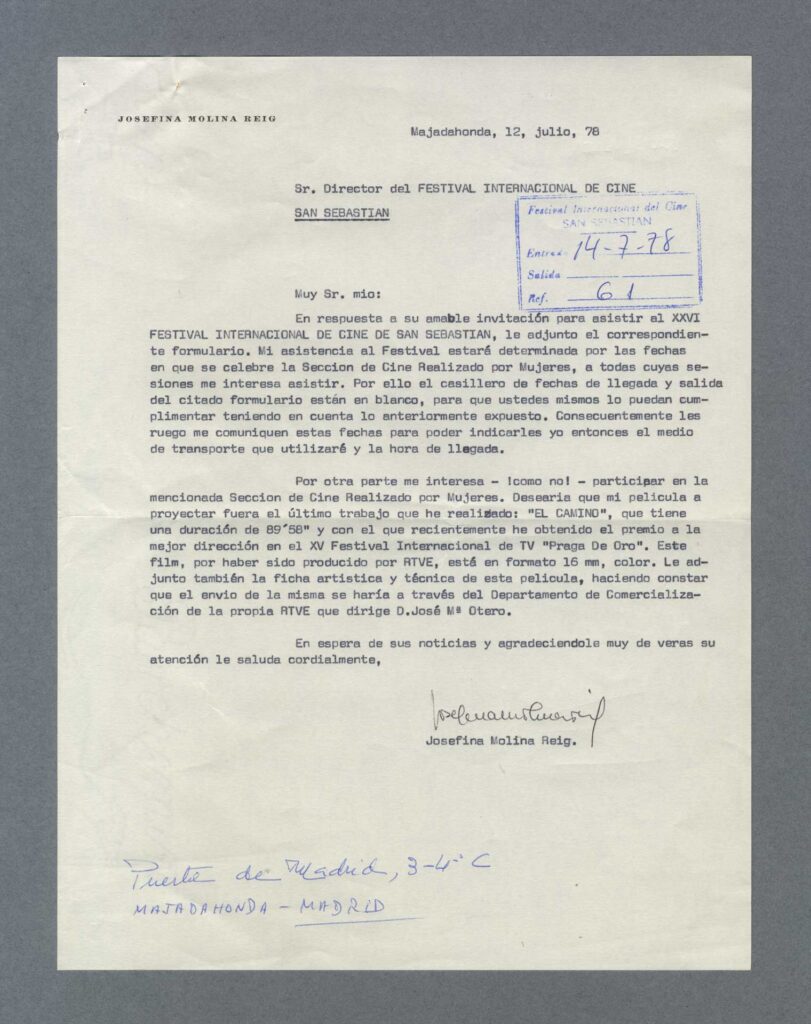

Letter from Josefina Molina to the Festival organisers (1978) San Sebastian Festival Archive [+]

[+]

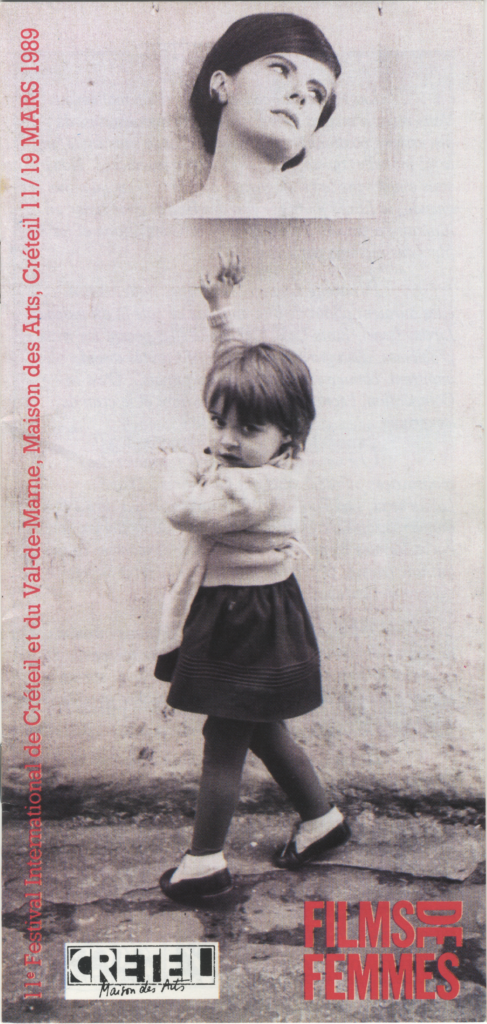

Program for the 11th edition of the Festival International de Films de Femmes de Créteil et du Val de Marne (1989) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

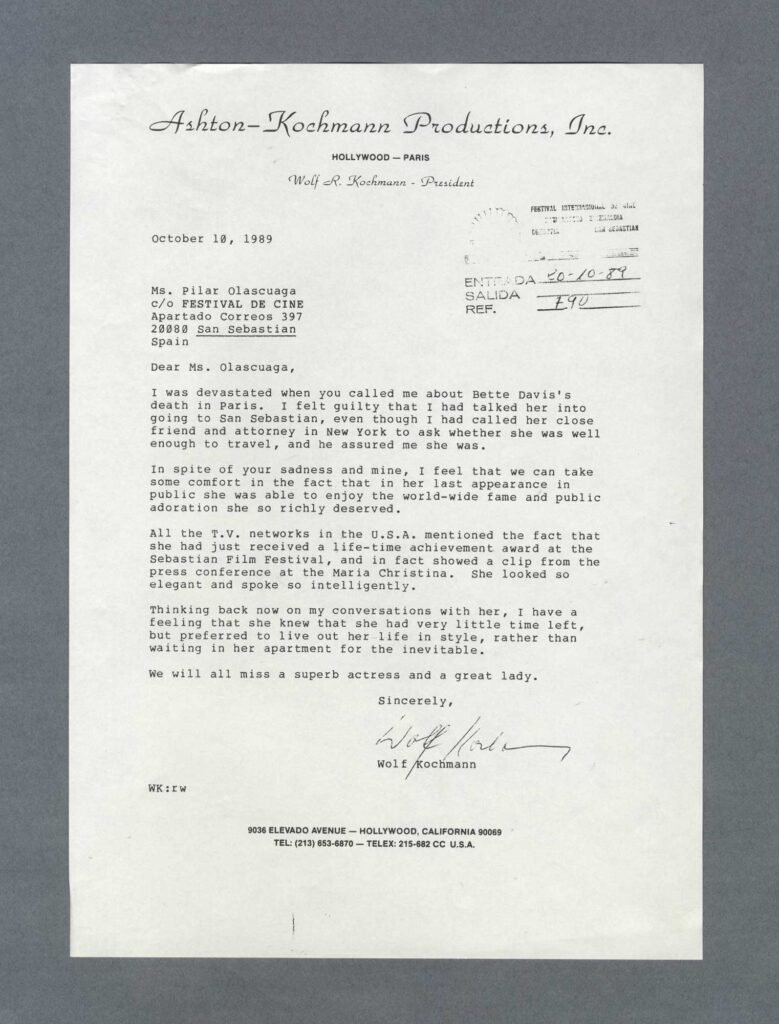

Letter from Wolf Kochmann to Pilar Olascoaga on the death of Bette Davis (1989) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

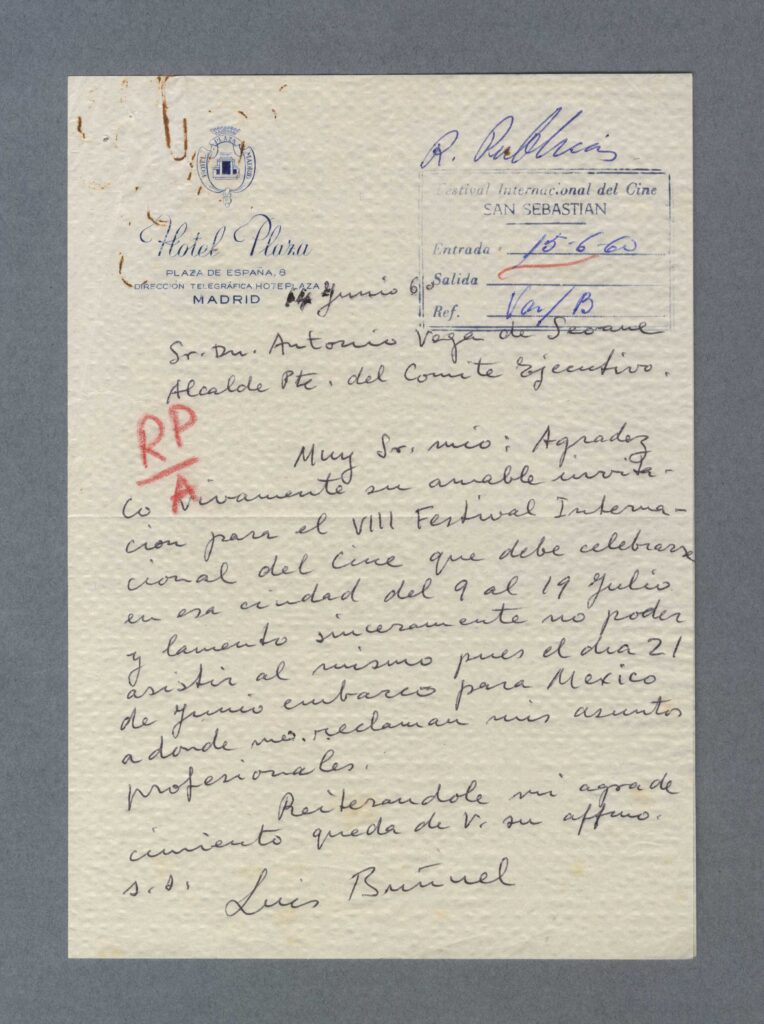

Letter from Luis Buñuel to the Mayor of San Sebastián Antonio Vega de Seoane (1960) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

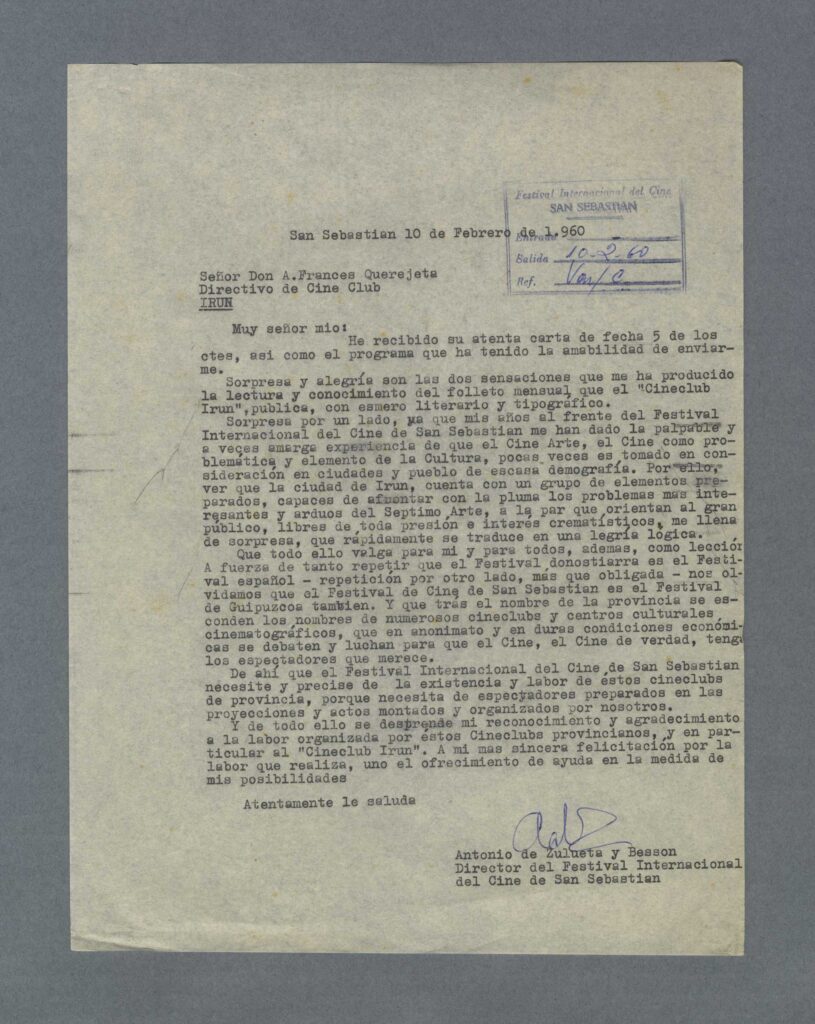

Letter sent by Antonio de Zulueta y Besson to the Cineclub Irún accepting to collaborate with them (1960) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

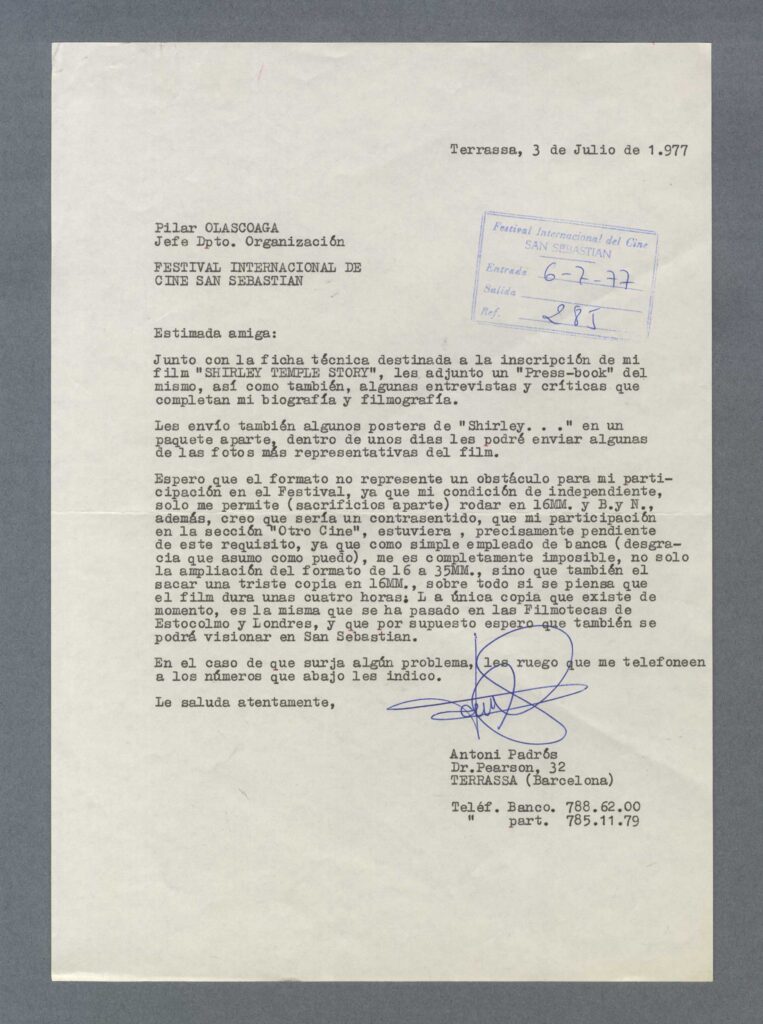

Letter from underground filmmaker Antoni Padrós to Pilar Olascoaga (1977) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

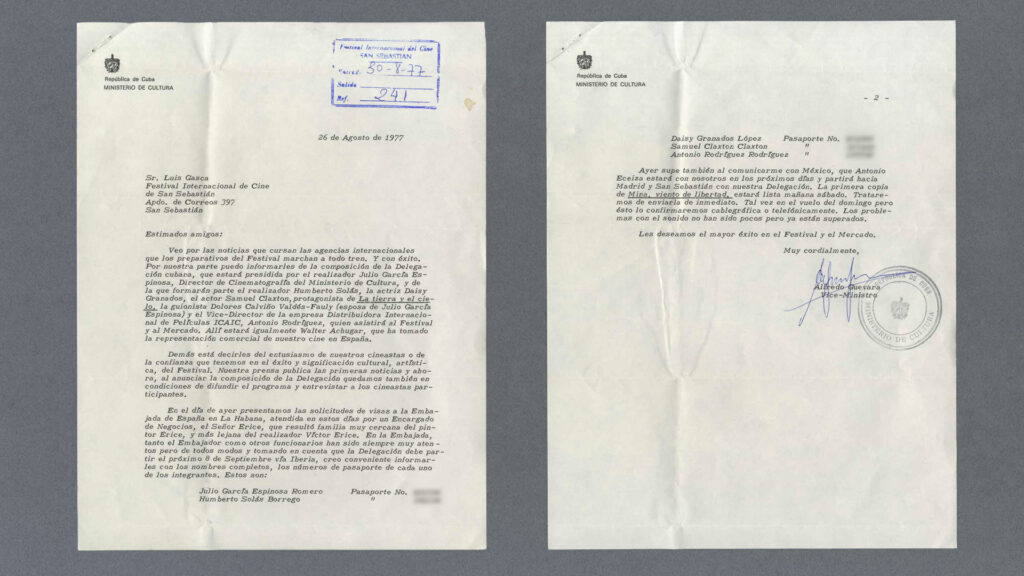

Letter from Alfredo Guevara, Vice Minister of the Ministry of Culture of Cuba and founder of ICAIC, to Luis Gasca, Secretary General of the Festival (1977) San Sebastian Festival Archive [+]

[+]

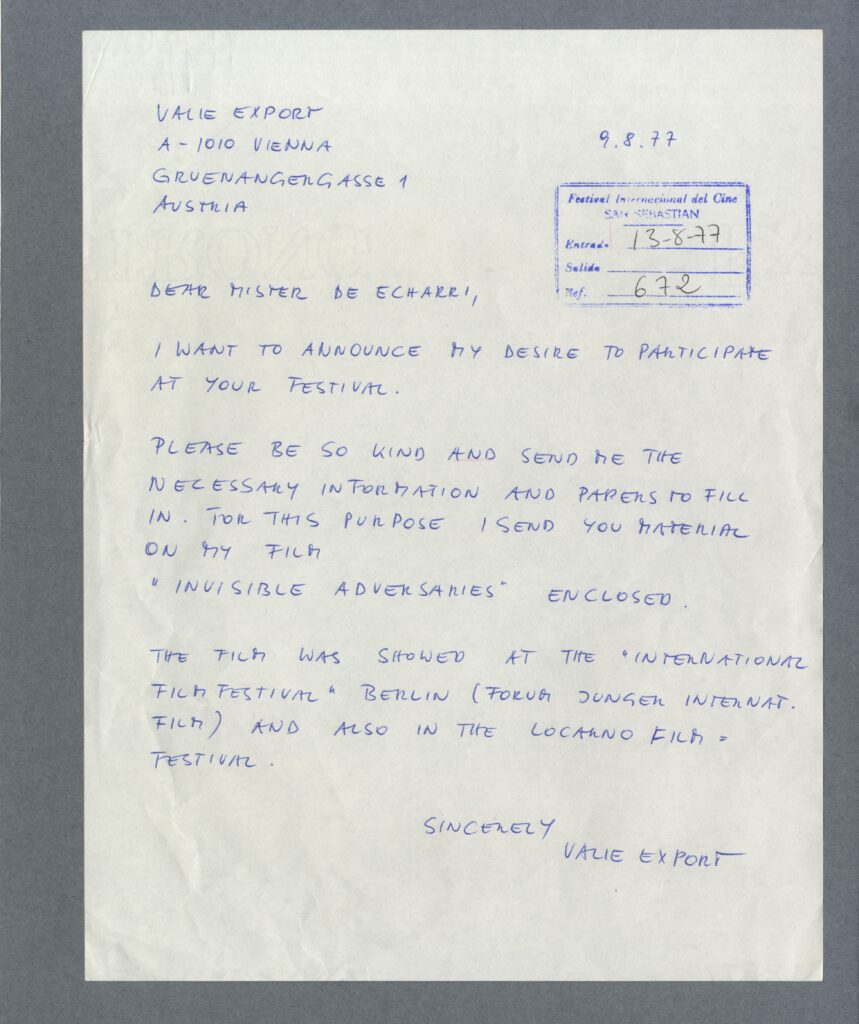

HLetter sent by VALIE EXPORT to Festival Director Miguel de Echarri (1977) San Sebastian Festival Archive [+]

[+]

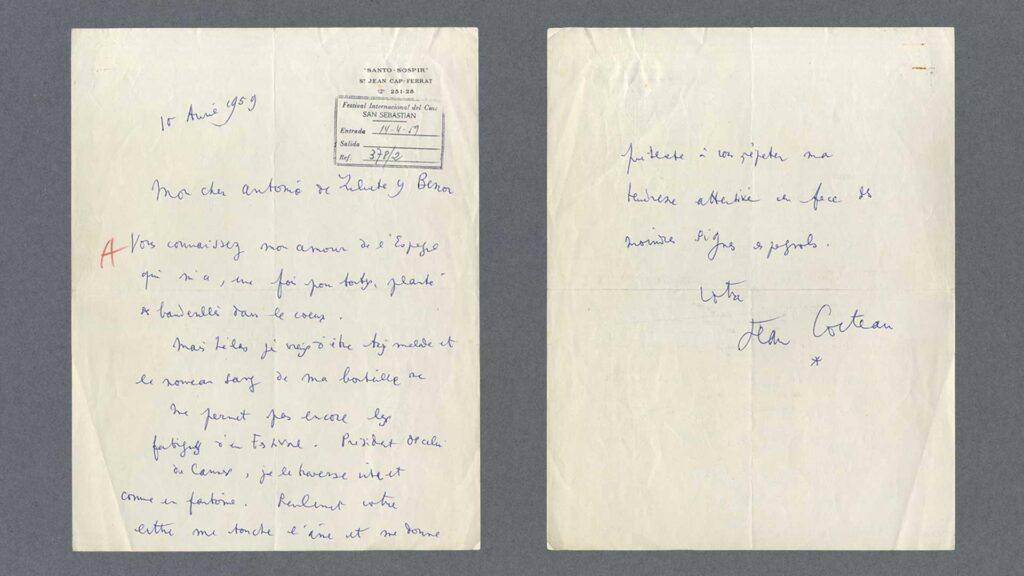

Handwritten letter from Jean Cocteau to Antonio de Zulueta y Besson (1959) San Sebastian Festival Archive [+]

[+]

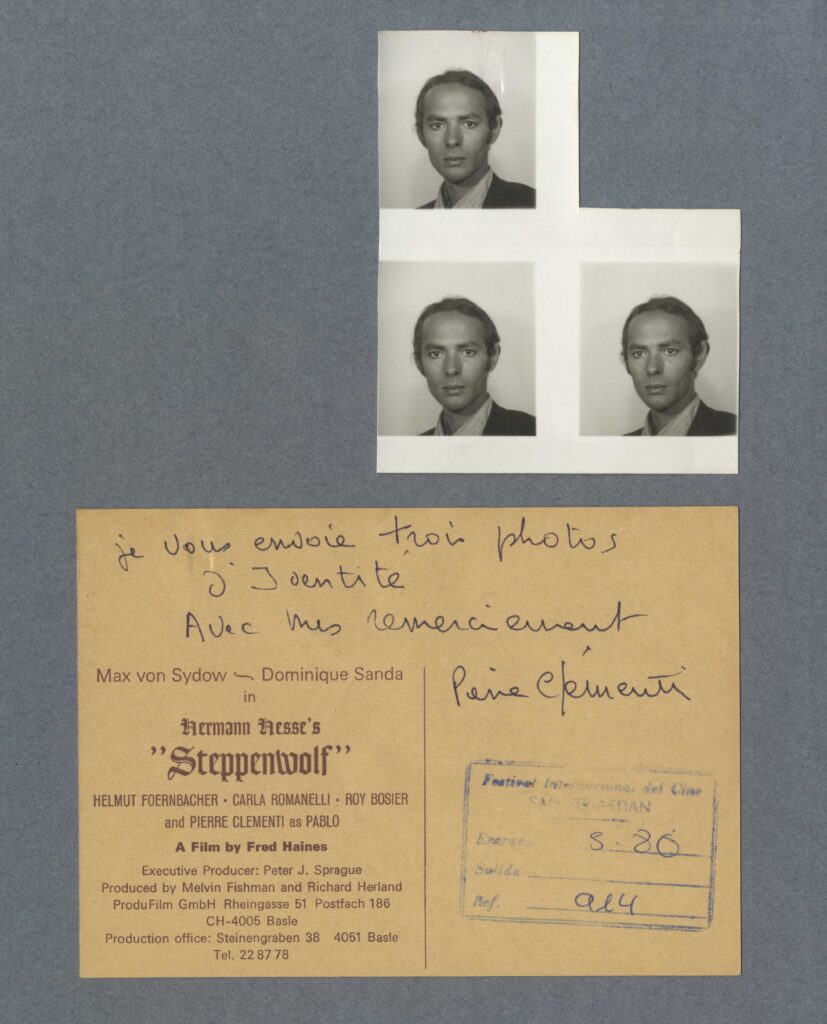

ACommunication with the director Pierre Clémenti (1979-1980) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]

[+]

Accreditation of Pilar Olascoaga to attend the 40th edition of the Berlinale (1990) San Sebastian Festival Archive. [+]