Organized by

In collaboration with

Sponsored by

Glossary, displays and some reflections on materiality based on the Video Festival Archive collection (1982-1985)

[Video: a common language, anything that refers to the handling and/or recording and/or reproduction of sound and image via magnetic procedures in a synchronic and simultaneous manner. A form of reference to magnetic audiovisuals. Abbreviation of videotape] (Antoni Mercader, 1982)

Between 1982 and 1985 the San Sebastian Film Festival launched an unusual experience: a festival within a festival – the Video Festival. During those years, Guadalupe Echevarria, director and founder of the project, invited artists from all over the world to participate in it. The contributions were very varied: some people programmed and installed works, others took part in debates on video and education, while some attended as representatives of cultural institutions, audiovisual groups or art galleries to see what was going on. The proposition was highly innovative and appealing for a video art culture that was emerging at the time. The Video Festival became a space for exhibition, exploration and learning that led to the creation of an artistic community around a new discipline.

The new practice brought its own language with it, which was necessary to understand its material nature. Antoni Mercader, the Catalan curator and artist who took on the post of Technical Director of the Video Festival, published an article called Breve léxico de la tecnología de video in Diario Video in 1982, laying out a series of terms in alphabetical order to explain the devices and handling processes involved in video art practice.

The importance of putting a name to things shows the primitive state of formal experimentation based on these elements and resources at the time (some of them taken from other areas) and indicates a common language of understanding that became a requirement for the community. Naming things is the first step in any new process, and the publication of the lexicon in newspapers not only showed the language that artists were using but also illustrated the need for these words to be taken on board by critics and understood by the general public. Something new was being born, and it need to be given a name.

Based on the discovery of this document-glossary, we were able to see how an entire series of manuals for installations, technical dossiers, factsheets and programmes in the Video Festival used the terms compiled by Mercader to describe the processes and their modes of exhibition. We came across many works that were accompanied by maps or guides explaining how the devices should be connected (TV sets, mixers, cameras, consoles, instruments) so that the installations could be staged. These documents reveal a creative and experimental era where many ways of rethinking filmmaking, video and art came together. Its potential for expansion was evident, together with the interest of a large community of artists who were beginning to explore a new practice that was far removed from the conventional aesthetics or narratives of filmmaking.

With Mercader’s publication acting as a guide, we propose a journey through the Video Festival Archive collection that will allow us to observe the new definitions and ways of thinking about art through this medium. Specifically, we will focus on five works that are important in the current scene. They are projects by Eugenia Balcells, Patrick Bousquet, Wolf Vostell, Jacques Lizène and Antoni Miralda, all of them multidisciplinary artists who focused on video at some time in their careers. We can see that the main medium they used to record images and sound was analog video with magnetic recording and reproduction. Magnetic tape is a data storage format that is recorded in tracks on a plastic strip with magnetized material. The kind of information that can be stored is varied: it was extensively used, for example, in TV programmes and domestic videos. To reproduce the videos in the works, most of the artists used a video tape recorder (VTR), a frequently mentioned component. It not only allowed the reproduction but also the recording of sounds and images. As Mercader explains:

[Video tape recorder: a transformative element in a video installation. It established the magnetic field that records video and audio signals in a synchronous way on the same format and reproduces them instantly. It is also called videorecorder or magnetic tape recorder]

Artists incorporated it into their processes due to its accessibility and production cost. With the use of this technical support device shared with TV, they also proposed an alternative form of communication that expresses active criticism of the mass audiovisual communication media. While the works we are looking at are very different in terms of subject matter, plurality helps us to understand how eclectic and multidisciplinary video took form, ideology and installation.

Key words: monitor, image, loop, audio, synchronization

In the Video Festival collection archive there is a dossier on From the Center by Eugenia Balcells. In this work, the Catalan artist, a pioneer in video art and experimental cinema, proposes an installation of 12 screens in which she presents 12 points of view that she records from her studio in New York. Balcells wrote a synopsis in which Echevarria intervenes, leaving some notes: “It is an exploration of multiple ways of seeing, looking in all directions from the same place. It is a personal vision, the interaction-relationships of 12 complementary views on the space around me. The 12 tapes that make up the work were recorded from the roof of my study on the corner of Bowery and Grand St. in New York”. Balcells’ work was installed in the Video Festival from 19 to 24 September 1983.

From the Center starts out as a centrifugal force that locates the camera as a panopticon that records everything in 360 degrees. It explores the many ways of looking in all directions from a single place, proposing a rupture in the point of view. It does not observe from just one plane (as in the cinema) but is perceived as an explosion of one’s gaze that proposes a circularity and a different way of understanding space and time. The dossier describes the graphics of the 12 screens and their location in the map in reference to the rest of the city of New York.

The technical components can be defined based on Mercader’s terms. On one hand, there are 12 monitors located in the circle in the space.

[Monitor: a reproductive element in a video installation. It reproduces the image and/or the sound respectively, on a luminescent screen of an iconoscope or a picture tube and a speaker, in accordance with the information received through the audio and video signals of the video tape recorder or the electronic camera (directly). If the signal is transmitted by radio frequency, the term used is ‘receiver-monitor’]

Each monitor reproduces an image that the artist records from her studio. These are street recordings.

[Image: Representation that is produced by the appearance of rays of light in a focused optical lens. Term used to describe the visual component within ‘audiovisual’. A complete frame that, according to CCIR, is formed by two fields of 312 1⁄2 lines that are produced alternately 50 times per second]

The images are reproduced constantly in a loop so that the work functions continuously. There is no start and finish; the spectator can enter the installation at any moment.

[Loop: A form of placing the magnetic tape in an endless ring, in order to obtain an uninterrupted reproduction. The English term loop is the most common one used]

From the Center not only records the corners of the city in an image, but it also reproduces the audio and the usual hustle and bustle of New York.

[Audio: Technological unit referring to aural behaviour. Electrical signal that transmits aural information]

The fundamental element of the piece is synchronization. All the monitors, together with the audio, are synchronized to generate the sensation of circularity of the city. Each tape is coordinated with the other.

[Synchronization: System that coordinates the obtaining of images and sounds consistent with the external reality one wishes to reproduce. Series of impulses superimposed on the information of the image on the video signal that regulates the magnetic fields of analysis and reproduction]

Key words: editing, post-production, blue-box, special effects generator, U-Matic, cassette

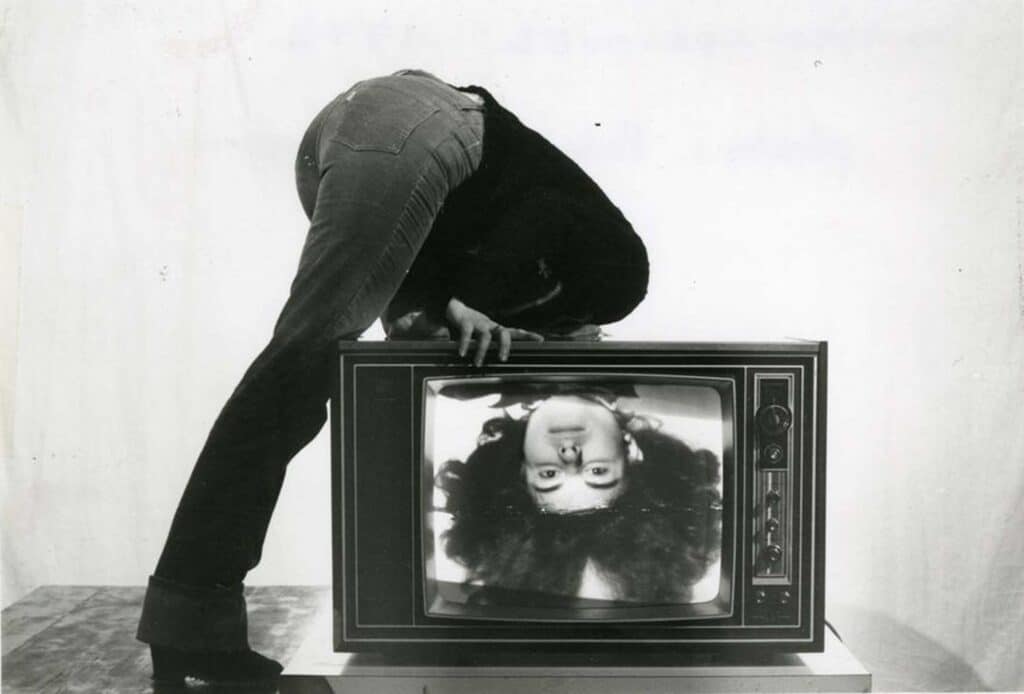

Patrick Bousquet and Michel Jaffrennou are two French video artists y performers that explore the possibilities of video applied to theatre. Les Toto-Logiques is a succession of sketches in which the artists make fun of the TV monitor. The apparatus and their images, as well as the two actors, are the protagonists of absurd and humorous situations where they perform with the object as if it represented something else. Monitors as furniture, or as magic boxes, water containers or fishbowls. They find the trick between what the square box (TV) is and the infinity of senses that can be assigned to it through the content of the video that they broadcast.

In the San Sebastian Film Festival Archive there is a file with catalogues that describe the places where their work has been presented, as a kind of letter of presentation for the interest of the Video Festival, although it is not among the informative files that confirm that the piece was exhibited in the festival. One of the main documents bears the name Stage de Vidéothéâtrie, and explains video theatre as a way of “staging video” as a different kind of dramaturgy.

In the file there is a record card of one of the video theatre works, Les Toto-Logiques, where the staging is described through an installation map, as a drawing of the specific requirements.

There are two monitors placed in the centre of the stage on some stools that reproduce the images with which the actors are going to interact. The synchronization between the action of the bodies and the video that reproduces them is essential to create the staged effect, as well as the sound reproduced by a stereo tape recorder (the same function as the video tape recorder for video, but in this case for a soundtrack). As they describe it, other theatrical elements in addition to the TVs are required such as curtains, the dividing bar and the distance measured for correct performance. The videos reproduced by the monitors are scenes that involve a lot of editing and post-production in order to generate the dialogue between the internal and the external (i.e. of the TV) with authenticity.

[Editing: Series of operations aimed at obtaining a certain succession of sounds and images. Involves the editing of sound and images, special effects, rubrics…]

[Post-production: Term that generalises all the tasks and work arising from the creation/production of a video tape or product]

The actors are filmed in studios against blue or green backgrounds that are then replaced in post-production by any other image through a blue box or chroma-keying process.

[Blue box: Effect. See Chroma-Keying: term in English describing the special effect that consists of inserting colour images (or a part of them) on another (also colour) image. This effect, called Blue Box, is achieved by the use of special blue colouring that enables insertion in colour]

This kind of effect could also be achieved with a special effects generator, commonly used for the broadcast of TV programs.

[Special effects generator, or mixer: Instrument that makes it possible to obtain certain visual and/or sound effects based on specific audiovisual information, without necessarily involving the recording function. Among the most common special effects are pit, keying, chroma keying, negative/positive, curtains…]

Within the description of the technical material, artists refer to U-matic. It was a format of cassette extensively used in video art due to its accessibility and compatibility.

[U-Matic 3/4: Registered trademark of a video-cassette system that used 1/4-inch tape and is the most compatible model, used for educational, industrial, artistic and scientific purposes, etc.]

[Cassette: Closed container around a tape. They are either coplanar (U-matic, VHS, Beta and Video 2000) or coaxial (VCR and SCR)]

Key words: closed circuit or mixer

The archive conserves one of the scores written by the German artist Wolf Vostell. Vostell was a multidisciplinary artist, a painter and sculptor, who was also one of the pioneers in combining video art with happenings and conceptual art. He was part of the Fluxus movement, an artistic current in visual arts that emerged in the 1969s and 70s. Fluxus artists were characterised, among other things, by translating performing art scripts into musical scores for events; this could not be further removed from what the instructions for La siberia extremeña V said. In the dossier we read that “a score is a place for each performer and soloist”, and Wolf Vostell also says that “there is also a complete score for all the material: ten 70×100 sheets for the exhibition in San Sebastian”. Wolf Vostell took part in the Video Festival on 22 September 1982 in a session titled “Kolnischer Kunstverein”, which brought together a series of German artists. Nevertheless there is no record that La Siberia Extremeña was installed in the years the festival was held.

From the content of the score we deduce that it is a work of great energy in which everything is connected; nothing exists in isolation. Each element is linked to the next one, proposing a much wider dialogue with other disciplines and forms of materiality.

Based on the lexicon proposed by Mercader, the technical needs to carry out the whole range of connections of the work seem to be the following:

The score presents us with a 45-minute event designed as a closed circuit, as a work that feeds off itself within the configuration of connections it proposes.

[Closed circuit: video installation that basically consists of an electronic camera, a video tape recorder (optional) and a monitor. It is used to give continuous information in a linear way. System of broadcasting TV signals via a coaxial cable]

Seven Sony colour video cameras are connected to seven microphones. The cameras record one of the soprano singers while the microphones are placed where the second soprano is located. Both the cameras and microphones are connected to a mixer.

[Mixer: instrument used in video laboratories to mix images and/or sound on magnetic recorders]

The public sees these images and sounds synchronized live on seven monitors. This is possible because the mixer is connected to a Sony U-matic video tape recorder that records the image and the audio of all the action that takes place. The performative installation consists of other elements on stage: a grand piano, an old piano, a pianist, a violinist, a dog and a tree (an olive tree), as well as the two sopranos mentioned above. Vostell himself is also part of the performance, playing the old piano.

Key word: portapack

The dossier on the Minable music-hall recital-performance by the artist Jacques Lizène includes a letter in which he presents the work, the technical needs, the expenses and fees that the Video Festival would have to pay so that the work can be shown in it. The Belgian video artist and singer defines himself in his dossier as [an] “artist of mediocrity, of unimportant art”. He mainly stood out for his musical career, into which he incorporated video art, although over the years he also explored sculpture, painting and performance. Minable music-hall[2] also ended up being the title of an experimental rock music disc (vinyl) that Lizène released in 1983.

In the Video Festival collection, the file on Jacques Lizène concludes with a letter from Guadalupe Echevarria in which she tells him that his recital-performance “seems very interesting, but unfortunately we only accept video tapes in the festival”[3], which leads us to think that the work was not presented. Even so, this proposition of a more musical nature includes technical elements of video art.

The installation consists of one or four monitors –depending on the version of the performance– that reproduce the audio and the video received via the video tape recorder. We deduce that the videos shown on these screens were recorded with a portapack, as it was the first portable video recording device (compatible with the U-matic format) and represented a revolution in the way of recording video. The appearance of the portapack allowed artists to record things in a lighter, more accessible way without the obligation to have to create in a studio. Its use therefore spread quickly among most of the artists as it gave then even more freedom in the recording of images and audio.

[Portapack: English term to describe a portable video tape recorder with a format no larger than ¾ of an inch]

In the live recital of Minable music-hall the audio is reproduced through a number of microphones. A stand-up microphone for the singer, another one that looks like a concrete mixer with marbles, and a synthesizer. All three are connected to a loudspeaker.

Key words: NTSC, Telecine

The El banquete de San SebasTVan (1984) video-installation project was created by the Catalan artist Antoni Miralda together with a group of chefs from San Sebastian at a time when New Basque Cuisine had really consolidated itself. In one of the documents in the dossier, Miralda explains to Guadalupe Echevarria that the work was originally going to be called Video/Tapas, although the new name seemed better because it was going to be made with well-known chefs. Miralda, who lives in New York, has already explored the potential of video applied to cuisine, and he would continue to experiment with it in later creations. Indeed, towards the end of the 1990s he created the FoodCulturaMuseum, a virtual museum focused on research, compilation, preservation and documentation of the many and varied connections between food, popular culture and art.

The idea behind El banquete de San SebasTVan was to elevate Basque gastronomy to the category of art. It was an installation project designed to export the potential of Basque cuisine in the context of the Video Festival, but also in international gastronomy fairs. The technical dossiers are dated in 1984, although there is no evidence that the work actually took place.

The moving images that make up the installation were shot in 16mm and then transferred to U-matic NTSC videos. The transfer from 16mm to U-matic was done through Telecine to convert the film image into magnetic image and sound, thereby making the editing of the videos easier as each video would alternate the preparation of a dish with iconic images of the city of San Sebastian (e.g. the effigy on the Church of Santa María del Coro, boats in the harbour, market scenes, bars in the Old Quarter…).

[Telecine: instrument that enables the transfer of chemical visual information (cinema and transparencies) and magnetic information (videotape or video disc)]

We deduce that a U-matic NTSC system was used so that the videos could be distributed to international TV channels.

[NTSC: National Television System Committee: used to describe the American system of magnetic reproduction in colour. The signals of the three primary colours are transmitted simultaneously and are later separated and distributed in the receiver-monitor].

The staging required a round table with six monitors on it connected to six video tape recorders that broadcast the audio in stereo through an amplifier and loudspeakers. On the table the screens were placed looking upwards, as if they were food trays, reproducing each 20-minute video, in colour U-matic format in a synchronized manner and in a loop. As we read in the dossier, the installation would be “a plastic work in which the treatment of images and colours highlights the work of the chefs in an artistic and creative way”.

The material available in the Video Festival collection of the San Sebastian Film Festival Archive reveals how artists of the time saw video as a medium of expression that allowed them a much freer and more spontaneous narrative, without the need for any clear or coherent structure. The image and the audio were subject to great freedom of expression, allowing experimentation from different places, ranging from editing and the introduction of special effects. Undoubtedly, however, the video artists looked for inspiration in other arts: performance, music, theatre, cooking. This shows that video art fed off –and still does– different disciplines, devices and materials that expand its narrative and artistic possibilities, beyond a mere TV broadcast.

Like the other avant-gardes that emerged in the 20th century, video had a political and counter-cultural position that was made possible from the way it experimented with language. A whole community of video artists, curators and programmers emerged who took it on themselves to circulate video through festivals, fairs and art centres. This led to what Mercader called the video sector:

[Video sector: a series of persons, atmospheres and/or relations that, based on a strict sector awareness –in the professional/trade association sense of the term– or not, promote, enable and work around the videotape in a sufficiently differentiated way and with a minimum historical perspective]

The Video Festival collection contains a record card of the work Bilbao la Muerte by the artist Juan Carlos Eguillor; it was exhibited in the festival on 19 September 1983. This report helps us to illustrate the freedom that the new medium represented for artists, as it contains a reflection in which he recognised that he was interested in video for “its immediacy and the certain ambiguity offered by its –at the time– lack of graphic definition”.

In a conversation between Guadalupe Echevarria and Pablo La Parra Pérez in June 2022, Guadalupe acknowledged that the artists of the Video Festival were seen as ‘the abstracts’ within the San Sebastian Film Festival: nobody really understood what they were doing. Faced with this abstraction, there was a basic need to offer words and forms for these video artists. This is why we find Mercader’s glossary useful, as it tries to explain some of the basic definitions of artistic practice used in the medium to the general public. This terminology laid the groundwork for naming a discipline that was growing. Although the words have mutated and taken on new meanings as a result of technological progress, together with the revolution of the digital medium and the appearance of the Internet, the lexicon proposed by Mercader allows us to understand the genealogy of the medium and the artistic processes of the time with their specific vocabulary.

[1] https://www.bnf.fr/fr/agenda/michel-jaffrennou

[2] Minable music-hall: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CggDoJfx-5g

[3] Letter from Guadalupe Echevarría to Jacques Lizène. San Sebastián Festival Archive, dossier FV.1982-1984.0115